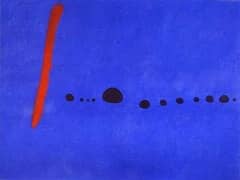

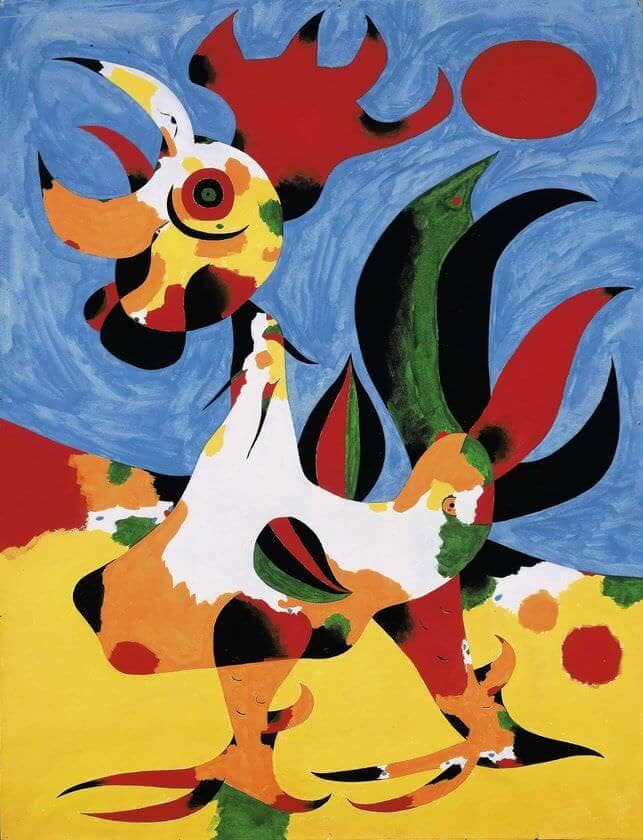

Le Coq, 1949 by Joan Miro

Le Coq was painted in Varengeville-sur-Mer, a village on the Normandy coast where Miro and his family sought refuge from August 1939 to May 1940, the beginning of the Second World War. 'At Varengeville-sur-Mer, in 1939, began a new stage in my work which had its sources in music and nature. It was about the time that the war broke out. I felt a deep desire to escape. I closed myself within myself purposely'.

Miro's rediscovery of the rural tranquility denied him since his exile from Spain underlies the painting of Le Coq, reproduced in the second volume of Verve. Nature as inspiration is reinforced by the accompanying text in the magazine: 'This the eighth number of Verve devoted to the nature of France was entirely composed during the war'. The figure of the rooster dominates the landscape, more evocative of Mont-roig than the Normandy coast, his head tilted upwards, sharp beak opens in a defiant cry. Pictorial urgency is heightened through Miro's limited, intense palette of colors. Red vibrates alongside green, while black, as a color area liberated from its traditional function as shading and contour, acts as a perfect counterbalance. Tension is evoked through the contrast in depth of the flat, saturated yellow earth with the painterly blue sky, the whole piece a mastery in color on par with Matisse, whom Miro credited with having 'taught us that color alone...could carry [a picture's] structure through contrasts and subtle juxtapositions' (quoted in J.T. Soby, Joan Miro, New York).

Miro conveys hope and optimism through the harmonious balance of black and white, the formation of the horizon as a band of contrasting colors, an extension of the rooster's body, uniting the earth and sky. Within the universal frame of reference, the airy blue of the expansive sky symbolizes hope and peace.