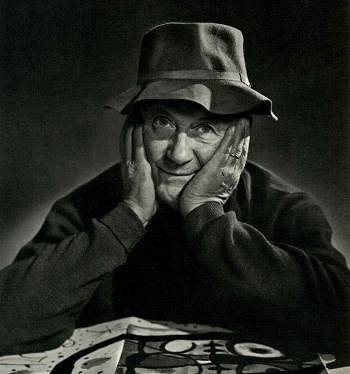

Joan Miro Biography

Joan Miro Ferra was an influential 20th-century painter, sculptor, ceramicist and printmaker, who was born in 1893 in the Catalan region of Spain, near Barcelona. He began drawing as a young boy, and later attended a

business school, as well as La Lonja School of Fine Arts. At the latter school, he was encouraged by two teachers; one encouraged him to revive the spirit of primitive Catalan art, combining it with modern discoveries and

techniques. (This was in the beginning of the 20th century, at the time modern art was just beginning in Europe, and the creative climate was energetic and progressive.) As a youth, he was exposed to the rich folklore of

Catalonia, which later influenced his images, such as how he saw all-natural forms as beings, including pebbles and trees. He was also exposed to complete interiors of ninth to twelfth-century frescoed churches in visits to

the Museum of Catalonia in Barcelona, with their relatively crude execution and their simple, flat and cartoon-like imagery. They also used primary colors, all heavily outlined in black, with a darkly shaded surrounding

field, as well as the also modern treatment of space as a flat surface rather than the traditional illusion of depth in an image (perspective, etc.). All of these elements can be seen in Miro's work, as well as the use of

differences of scale, where one form is disproportionately larger than others, a method often used by children when they make the objects most important to them the biggest objects in the image.

After 3 years of business school, Miro took a job as an accounting clerk in a drugstore, which was the type of position his parents chose for him. He was overworked there, and became seriously ill, verging on a 'nervous

breakdown,' followed by a bout of typhoid fever. His parents then took him to their new country farm, Montroig, in a secluded village in Catalonia. The state of his health caused his parents to allow him to do what he most

wanted to do - paint. He attended the Academy Gali in Barcelona (a free-spirited academy with the influence of contemporary foreign painters, where there was also interest in literature and music). The individual

expression was encouraged; Miro also learned to draw by the sense of touch alone, rather than by sight. At this time (around 1915), Dada was beginning, and Miro began reading avant-garde Surrealist poets such as

Apollinaire and Pierre Reverdy. He met Josep Llorens y Artigas, who was to become a lifelong friend, and with whom he was to collaborate in pottery projects in the years to come. Miro was also influenced by Fauvism

(specifically Henri Matisse) and Cubism, which started in the early years of the 20th century, and at first painted still lifes. (Spain has a historical tradition of mystical still

lifes, which combine commonplace objects with eerie lighting against total blackness.) From 1915 to 1918 he painted nudes, then portraits, then landscapes. At this point, he began "geometricizing" the forms, and used colors

independently of their local color (like the Fauves, who used bright colors not seen in nature). He also began searching for signs and symbols to represent humans and animals in tension or movement. His two biggest

influences when young had been Paul Cezanne, Manet, Claude Monet, and

Vincent van Gogh. The Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona was a gathering place for foreign visitors; here Miro met Francis Picabia, a Dadaist painter. Miro's work had gone through a period

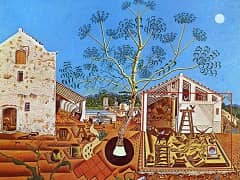

of free expressiveness; he now decided to tighten up somewhat, doing landscapes until 1921-22. His best-known work from this period is The Farm, a view of his parents' farm. The work done during this

time shows minute details, using the precision of a naive primitive painter. At this time, and all his life, he was influenced by his Catalan heritage, such as the decorated Catalan pottery, and the Catalan murals which were

restored in the 1920's, and painted in flat patterns in a folk style. He was also at this time beginning to be influenced by Surrealism (which began in the 1920's), and his work now took on a more spare look (paring down to essentials).

In 1919 he took his first trip to Paris, visiting Picasso in his studio. The painters Francis Picabia, Salvador Dali, Antoni Tapies, and the

architect Antoni Gaudi were also born in Catalonia. Although Picasso was born in Malaga, in the Andalusian region of Spain, he was influenced by Catalan art. In Miro's life, there were three important places: Montroig (in

Catalonia), Barcelona and Paris. (Catalonia is located in the northeast part of Spain, close to France, and Catalan culture is very close to the culture of the south of France. The Catalan people have always been very

independent people, holding fast to their language and traditions.) One year later, he visited Paris again, meeting Surrealist poets Pierre Reverdy and Tristan Tzara. At this time he attended the first Dada demonstration

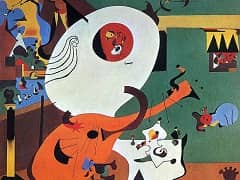

in Paris. And finally, he moved to Paris, at an exciting time for young artists, who shared a supportive friendship. In 1923, there was a big change in Miro's art, moving toward more sign-like forms (i.e., like hieroglyphs),

geometric shapes, and overall rhythm. There was also a move toward a more overall composition, with The Harlequin's Carnival of 1924-25. This overall type of composition was later used by

Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko and other modernists; rather than using a focal point such as that used in traditional painting,

the composition encompassed the entire picture surface equally in all places. His forms included cats, butterflies, mannequins, and Catalan peasants, and there was visual movement in his images. Surrealism began at this time,

with the writer Andre Breton issuing the Surrealist Manifesto. Surrealism was supposed to be a fusion of reality and the dream, a sort-of "super" reality. Breton felt that Miro's work had an innocence and freedom about it. Miro showed his work

in Surrealist exhibitions, and was influenced especially by the Surrealist poets, who in their quest to tap the unconscious mind played games like the "exquisite corpse" in order to compose poems. Exquisite corpse was a

technique where a dictionary was passed around in a group of poets, who would each choose a word randomly from it. Whatever words came up, they would organize into a poem; this is how the phrase "exquisite corpse" was

created. They also used the techniques of psychic automatism (like free association), and "systematic derangement of senses." Miro and other painters (such as Andre Masson) worked out a way to transfer these techniques to

their visual medium, using their dreams and visual free association. Miro painted about 100 paintings from his dreams at this time; this was his most Surrealist period. He also illustrated Surrealist poems in collaborations

with poets. Another concept introduced by the Dadaists was the element of chance or accident in art. They would start with a splotch of fluid, then add to it to make a painting. "The painter works like the poet; first the

word, then the thought," is a quote that tries to describe how artists and poets may see or think of a concrete image or word, before they have formulated the idea or "symbolism" behind it. At this time, Miro was influenced

by the work of Francis Picabia and Giorgio de Chirico. Although he exhibited with the Surrealists, and was friends with many of them, he never submitted himself totally to their movement, and did not sign the Surrealist

Manifesto, perhaps because of the radical political activities of the Surrealists, who were also very interested in the psychological ideas of Sigmund Freud and Jung.

In 1927 and 1928, Miro painted figures derived from Catalan folk art. In 1928 he began painting images based on postcards of some Dutch interiors he had seen in Holland, by such painters as Jan Steen. The images he worked

from were crowded with forms; he gradually simplified the forms and stripped the image down greatly, using geometric divisions and curving movements in the compositions. At this time he moved further away from his points

of departure, and began using unusual sources, such as a diesel motor, influenced by Surrealist thinking. From 1928 to 1929 he produced a number of collages; in Paris he had moved closer to Max Ernst,

Rene Magritte, Paul Eluard and Jean Arp, so was influenced more by the work of these Surrealist painters and one poet. Max Ernst in particular is known for his collages. In

Surrealist art there were two tendencies: the representational imagery of Dali and Magritte, and the more abstracted images of Masson and Miro, though both were affected by Surrealist ideas of anti-logic and the

subconscious; and Dali's and Magritte's images, though painted in a highly realistic fashion, depict objects and scenes which do not appear in the rational world, such as a train coming through a fireplace into a room, or

melting clocks. By 1929, Miro had finished the first phase of his art-making, and he began to question and reappraise his work during the following 10 years, which were a struggle for him, financially and artistically. He

began experimenting with materials - doing papiers colles and collages, using pictures of ordinary objects such as household utensils, machines, and real nails, string, etc. This period of experimentation helped him to

drop any lingering traditional practices, and eliminate usual habits of working. By using objects of no significance, artists are able to concentrate on the abstract qualities of objects, rather than their associated

meanings or emotions, allowing for more formal freedom; the viewer also is less able to attach literal meanings to the images. These "neutral" subjects with little aesthetic value or significance take the attention away

from the subject matter and toward the forms and content in the image. After creating these collages, Miro would make a painting of the collage - transferring a flat collage image onto the equally flat canvas. These paintings

from the collages are highly refined and strongly graphic images, and even though they contain no identifiable subject matter, the paintings do contain content, or meaning. Although Miro is often characterized as an

abstract painter, he himself considered that he was not - he even felt it an insult to call his work abstract, since he claimed that every form in his images was based on something in the external world, just simplified

into his characteristic biomorphic shapes and curving lines. In the 1930's, conflict was active around the world, in particular the Spanish Civil War and the beginnings of World War II. Many atrocities occurred during the

Spanish Civil War, inflicted by Franco's fascist forces, as depicted by Picasso in his famous Guernica. Although Miro was not a political artist, his forms during this

time depict certain brutality, with distortions and garish color. He created a mural for the Spanish pavilion at the Paris Exposition of 1937, called The Reaper.

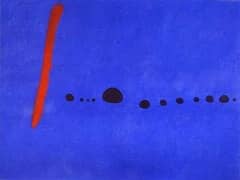

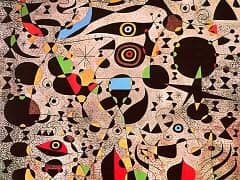

In 1940 and '41, he began his well-known series of 22 Constellations, which consist of black dots representing stars on a white ground, using gouache and thinned oil on paper. These are very intricate works, with every

part of the canvas activated. The carefully placed dots create a 'jumping' or 'dancing' sense of movement, even a "connect the dots" feeling. They remind views of late work of

Piet Mondrian, when he discovered American jazz - Broadway Boogie-Woogie of 1947, which has the same visual

movement, and a cool, dancing quality of the little squares. However, Miro's work tends toward more of cosmic awareness - these are stars, rather than just abstracted dots (painted poetry).

Miro stayed in Spain during World War II, his work is influenced by the night, music and stars. His forms became even more abstracted, and he used a number of techniques in his work, for example whenever lines

intersected, there was a splash of primary color; when red and black overlap there is yellow. He gave the works evocative titles such as The Beautiful Bird Revealing the Unknown to a Pair of Lovers. In 1942 he began his

interest in engraving and ceramics (with his friend Artigas, a highly skilled potter), and in 1944 he returned to painting, now adding a calligraphic quality to his images. By now he was beginning to gain international

fame, due to his 1941 retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and his presence in the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1947 in Paris, organized by Marcel

Duchamp and Andre Breton. That year he was invited to do a mural commission for a hotel in Cincinnati, Ohio, which was 30 feet long. In 1950 and '51 he did another mural for the Graduate Center at Harvard, which consisted

of loosely squared blocks of color combined with black lines and small areas of pure color. These elements form cartoonish figures. (This mural was later replaced by Miro's ceramic mural.) During the 1940's he also painted

some "stick figures," and in the 1950's his images contained forms that were almost like primitive pictographs. In his paintings, forms often do not touch the edges of the picture area - most are an even distance away from the edges, with perhaps one small element touching the edge of the canvas at the top or elsewhere. His backgrounds also have become more mottled now, rather than flat areas of paint, which gives the images more of a sense of visual depth. Despite not contacting the edges completely, his forms at this time still manage to have an overall type of composition. He also began painting ceramics during this time.

After the War, after having been in seclusion, he spent time with artist friends Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Calder and Yves Tanguy in New York. He was influenced by his time in America, particularly by life in the City of

New York, which consisted of bright lights and a kind of sensory bombardment, sometimes stressful. In 1948 he returned to Paris and had several exhibitions. Some of his works now are carefully composed and executed, and

others are deliberately spontaneous and experimental. In the early 1950's he began to merge these two tendencies in his work, with a painterly background, linear black and white forms, and touches of pure color. During the

1950's he developed a brand new approach, using the painting methods of primitive man, making painted and carved forms. At this time, he had his lifelong dream of a "big studio" made a reality, and he surrounded himself

with all of the objects he had collected over years in walks, such as polished stones, driftwood, seashells, horseshoes, farm implements, etc. This also reflected the Surrealist interest in special, magical objects, like

talismans. Their simple forms encouraged the simple forms in his work. From 1945 to '50, he had carved small figures in clay, like primitive fertility goddesses, and simple vases of bird and head forms. Between 1954 and

1960 he produced his greatest ceramic output, with the aid of Josep Llorens y Artigas, who provided technical expertise for his creations. They had the use of a very large kiln for Miro to bake his increasingly large

ceramic forms, which he created in individual parts to be reconnected after firing. They wanted to produce ceramic works which were not simply paintings transferred to ceramic, but in deference to the ceramic medium itself.

Their big project was to convert Miro's art objects to the ceramic medium. They started with large stone blocks suggested by natural rock formations in the countryside, then did small pebble and egg forms. They made vases,

dishes and bowls, and added forms to these, to produce objects of no practical use. Finally, he created entirely invented forms. They developed a highly refined glazing process, using 3 to 8 firings for each piece. Because

of the unpredictability of a kiln, pieces may fall apart or bring unexpected results. The use of the raku method of pottery, baking with a wood fire, produces effects not seen with gas or electric kilns. Miro learned to

control these whims of the kiln to a great degree, and there resulted 232 pieces, which he sent to Paris in 1956 for a show at the Galerie Maeght. The effect of this show in the gallery was powerful, having a strong effect

on viewers - his primitive forms standing and sitting throughout, like a paleolithic forest. Miro also produced his first bronze sculpture at this time. In 1955 he was commissioned to decorate UNESCO's new building in

Paris; he made a ceramic design in keeping with the building's design. For this project, he and Artigas inspected the cave paintings of Altamira and Romanesque frescoes in the Barcelona Museum, as well as the architect

Gaudi's decorations. Miro was awarded the Guggenheim Prize in 1958 for this work.

In 1959 he returned to painting again, and his work was now informed by his experiences in other mediums. In 1962 he painted Mural Painting III, an extremely spare image having a solid yellow-orange surface, with two small

black dots and three irregular lines, a spare, painterly image. During the 1960's he devoted more time to the mediums of printmaking, ceramics, murals and sculpture. One reason for his interest in these other mediums was

that they involved collaborating with other people, rather than the solitary activity of painting. Also, printmaking's production of many images rather than just one original appealed to him.

Miro's influence on the art of the later 20th century is great; some artists who were influenced by him include Robert Motherwell, Alexander Calder, Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock,

Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and expressive abstract painters. Perhaps the original color field painter was Matisse, and perhaps Miro's

use of a large field of color was due to Matisse's influence. Painters who came afterward who use the color field include Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski and Morris Louis. Miro's vast fields of color also introduced the

idea of "empty" space being as valuable as occupied space in painting. Here is a 1958 Miro quote from Twentieth-Century Artists on Art:

The spectacle of the sky overwhelms me. I'm overwhelmed when I see, in an immense sky, the crescent of the moon, or the sun. There, in my pictures, tiny forms in huge empty spaces. Empty spaces, empty horizons, empty plains - everything which is bare has always greatly impressed me.”

His characteristic biomorphic form was also influential in 20th century abstraction, with Alexander Calder and others. Miro had a unique place between Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism, influencing the New York School

of painters in the 1940's and '50's. Throughout his life, Miro worked in several printmaking processes, including engraving, lithography and etching, as well as the use of stencils (called pochoir). He stated that

printmaking made his paintings richer, and gave him new ideas for his work. In 1967, Miro was introduced to carborundum (silicon carbide engraving); combining this technique with other printmaking processes, he was able

to produce images that rivaled the original qualities of painting. He continued to explore the carborundum aquatints for the rest of his life, and in 1970 the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition specially

devoted to these prints. In his later years, he spent most of his time doing etchings, doing large-scale aquatints and book illustrations. Much of his work can be found in the Guggenheim

and Museum of Modern Art in New York. During the 1970's he continued to receive wide acclaim, and had major exhibitions in the Musee National d'Art Moderne, and other major art institutions in Europe and America. In 1980,

King Juan Carlos of Spain awarded Miro the Gold Medal for Fine Arts. In 1983, the year of his 90th birthday (and his death), there were birthday celebrations for him in New York and Barcelona.

In 1972, the Fundacio Joan Miro, Joan Miro Foundation was legally constituted in Barcelona. The museum opened in 1976, with a collection of Miro's drawings. A large selection of Miro's paintings, sculptures, textiles and

prints are exhibited there, as well as exhibitions of other modern and contemporary artists. In the book Painters on Painting, Miro is quoted in an interview of 1947, saying that his favorite schools of painting are

the cave painters - the primitives. He claimed at one point that since the age of cave painting, art has done nothing but degenerate. He also expressed a liking for Odilon Redon, Paul Klee and

Wassily Kandinsky for their "esprit." For artists of "pure" painting, he preferred Pablo Picasso and

Henri Matisse, and felt that both of their points of view are important. He added that the direction painting ought to take was to "rediscover the sources of human feeling." He

also stated that he made no distinction between painting and poetry, and that painting is "like making love - it is an exchange of blood, a total embrace - reckless and defenseless." He said his aim was to help painting

advance beyond the easel, to push its limits; to create a response first of physical sensation, then a great impact on the psyche of the viewer. He considered pure abstraction to be an absurdity, and empty. Like Gaudi, Miro

was fascinated with the Catalonian language; he demanded in his will that his funeral be held in Catalonian style with the obituary written in the Catalan language.

Miro's images, which came from his memory, the unconscious, dreams, and transformative modernist art processes, are at once childlike, innocent and sophisticated. His two poles of existence, Catalonia and Paris, reflect

this combination of rural and cosmopolitan. His forms (creatures such as people, birds, insects and animals) are whimsical and expressive, as well as inventive. The ultimate meaning of all of his abstracted realities may

not be known, but it's safe to say that they all had a meaning for him, in his childhood, in his dreams, and in his life.